Basic Explanation of Realism in IR

Introduction

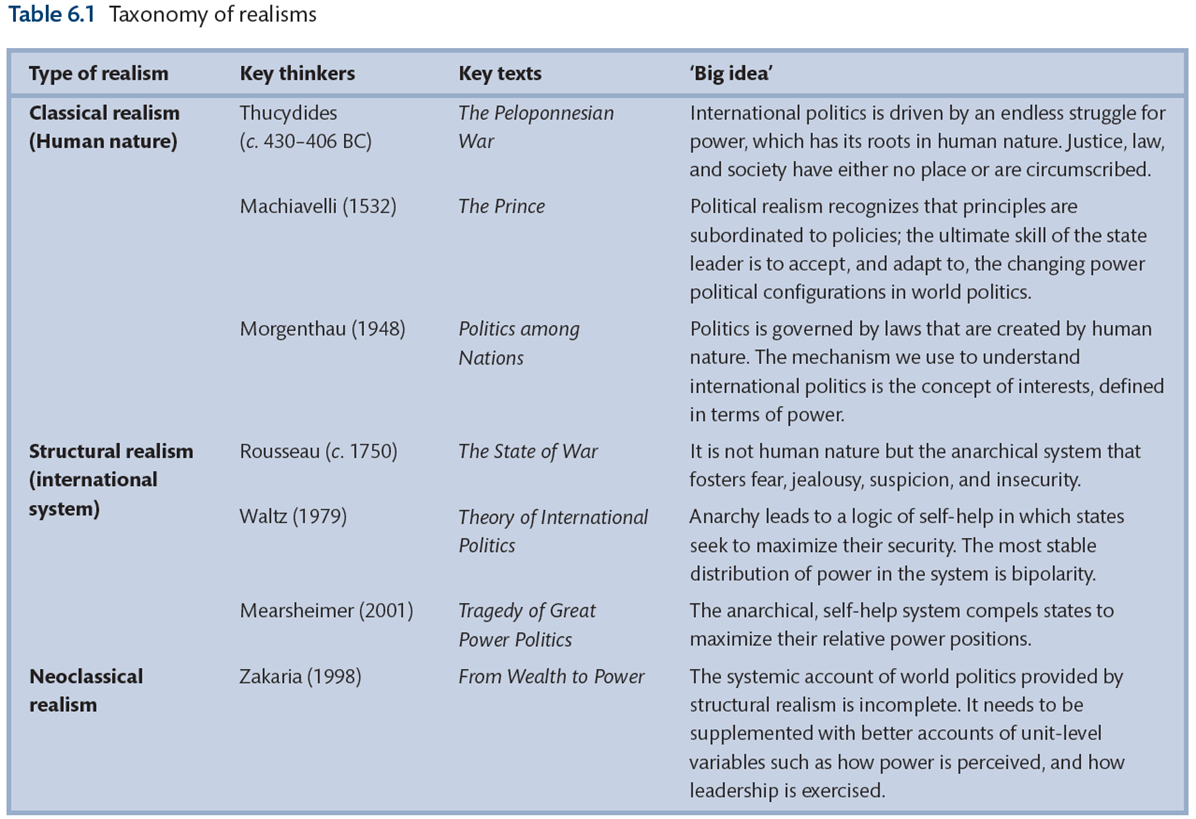

Realism is an influential tradition in the study of world politics deeply rooted in classical philosophy. It emphasizes statism, survival, and self-help as core tenets shaping relations between states in an anarchic international system.

Realism posits that sovereign states are the main actors in global affairs who operate in a self-help world where power is crucial for survival. International anarchy prevails beyond a state’s borders, meaning there is no central authority to regulate interactions. This forces states to pursue power independently as a means of safeguarding their security and interests.

The realist framework views states as unitary rational actors seeking to maximize self-interests defined in terms of power. Relations between states take the form of a struggle for power within a balance-of-power system, as they compete to prevent the rise of hegemony. Ethics and morality are secondary concerns, and leaders may disregard universal ethics in pursuit of state interests and security.

Historical Roots

The tradition of realism has deep historical roots, drawing inspiration from classical philosophers such as Thucydides and Machiavelli. Thucydides, an Athenian historian and general from the 5th century BC, is considered by many to be the founding father of realist thought. In his seminal work, The History of the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides presented a starkly pessimistic view of human nature and international politics. He saw power and self-interest as the main drivers of state behavior, with justice and morality subservient to survival. According to Thucydides, states exist in an anarchic realm where the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.

Several centuries later, Machiavelli also espoused fundamentally realist ideas in his influential book The Prince. Writing during the Renaissance period in Italy, Machiavelli focused on securing and maintaining power in a chaotic world. He prescribed cunning, deceit, and ruthlessness as necessary tools for effective statecraft. Machiavelli dismissed conventional morality as an obstacle to survival and portrayed the endless quest for power as fundamental to political life. His maxims, such as “it is better to be feared than loved” encapsulated his realist ethos.

Thucydides and Machiavelli planted the intellectual seeds of realism by stressing power politics, national interest, and survival as the essence of international relations. Their bleak realism continues to influence the worldview of modern realist thinkers and practitioners of statecraft. The roots of the realist doctrine run deep in the annals of human history.

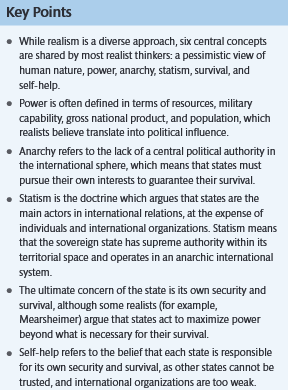

Types of Realism

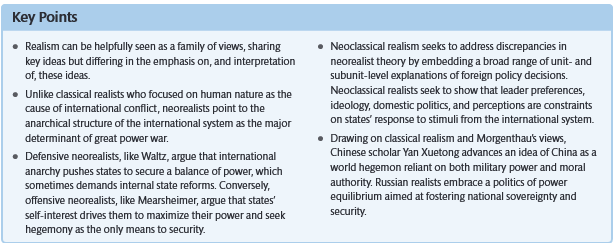

Realism encompasses different strands that share core assumptions but differ in focus and emphasis.

Classical Realism

Classical realism has its roots in ancient Greek thinkers like Thucydides and Machiavelli. It sees power politics and struggle between political communities as an intrinsic part of human nature. The key emphasis is on prudence and statecraft in navigating the challenges of international anarchy. Morality and ethics take a back seat to raison d’etat or national interest.

Structural Realism

Structural realism, also known as neorealism, gained prominence in the 1970s and 1980s through scholars like Kenneth Waltz. It attributes conflict and competition in world politics to the structure of the international system rather than human nature. An anarchic structure with no overarching authority leads states to be concerned about security and survival, promoting self-help and power maximization.

Neoclassical Realism

Neoclassical realism emerged in the 1990s as an attempt to incorporate elements of classical realism back into structural realism. It argues that systemic pressures constrain and shape, but do not completely determine, foreign policy choices. Unit-level factors like leaders’ perceptions and domestic politics also play an important role in how states respond to threats and opportunities.

Key Assumptions of Realism

Realism makes several key assumptions about international relations:

States as Primary Actors

- Realism sees states as the main actors in international politics. The state is viewed as a unitary rational actor that aims to pursue its national interests and maximize its power.

- Individuals, international organizations, and non-state actors are not seen as significant. Their goals and actions are secondary to the motivations and behaviors of states.

Anarchic International System

- Realism posits that the international system is anarchical in nature. There is no overarching authority that governs relations between sovereign states.

- This creates a self-help system where states can only rely on themselves to ensure their security and survival. The lack of a central authority leads states to be suspicious of each other’s motives and actions.

Centrality of Power

- In an anarchic system with no higher authority to resolve disputes, power is seen as the main currency of international relations. Power largely determines a state’s ability to secure its interests.

- States seek to maximize their share of world power relative to other states. This creates an endless competition, with nations striving to gain power at each other’s expense.

- The distribution of power capabilities among states shapes the dynamics of the international system at any given time.

Criticisms

Despite its prominence, realism has faced criticism over the years for its inability to fully explain complex international phenomena. One key criticism is realism’s failure to anticipate the largely peaceful end of the Cold War. Realist theory predicted an eventual clash between the two superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union, as they competed for power and influence. However, the Cold War ended not through military confrontation but through internal reforms in the Soviet Union and a resetting of relations between the two powers. Realism does not account for how cooperation, trust-building, and diplomacy helped avoid direct conflict and pave the way for a peaceful resolution.

Additionally, realism struggles to explain conflicts within states rather than between states. Realist theory focuses on states as the key actors in an anarchic international system. However, in the post-World War II era, the majority of conflicts have been civil wars, insurgencies, and intra-state violence. Realism does not provide analytic tools to understand the complex ethnic, religious, and ideological factors fueling these internal conflicts. Power dynamics between states cannot fully capture the grievances, motivations, and goals of non-state actors fighting internally over resources, representation, and rights. Realism is state-centric and often discounts sub-state and transnational forces shaping world politics.

Neo-neo Debate

The neo-neo debate emerged as a central theme of international relations theory during the 1980s following significant geopolitical shifts. This schism represented a clash between neo-realist and neo-liberalist paradigms in interpreting global developments.

On one side, neo-realists emphasized structure and anarchy as the key drivers of state behavior. They questioned liberalism’s ability to explain cooperation absent hegemonic stability. Neo-realists like Kenneth Waltz argued that the structure of the international system, defined by anarchy and the distribution of power, compelled states to maximize power and pursue self-help for survival.

In contrast, neo-liberal institutionalists like Robert Keohane posited that institutions could facilitate cooperation even without hegemony. Neo-liberals highlighted the role of international regimes and norms in shaping state preferences and interests beyond structural factors. Complex interdependence, they argued, made conflict increasingly costly and cooperation mutually beneficial.

This academic debate paralleled policy disagreements about engaging with the Soviet Union and China. The neo-neo divide framed analyses of major world events like the end of the Cold War, which neo-liberals viewed as showing the triumph of institutions over structure while neo-realists saw power dynamics as decisive.

The neo-neo debate profoundly impacted international relations theory, forcing engagement between structural theories and models acknowledging ideational factors. Later approaches incorporated insights from both neo-realism and neo-liberalism in explaining state actions. However, divisions remain between rationalist paradigms prioritizing material structure and constructivist frameworks emphasizing identities, norms, and ideas.

Structural Realism

Structural realists emphasize how the structure of the international system shapes foreign policy choices. Specifically, they focus on the anarchical nature of the international system and the distribution of capabilities between states as the key drivers of state behavior.

Since there is no central authority above sovereign states, the international system is essentially anarchical. This creates inherent insecurity and uncertainty, as states cannot fully trust one another. Structural realists argue that this sense of insecurity encourages states to compete for power and influence as a means of survival.

In addition, the distribution of capabilities (such as military and economic power) is critical. States are especially concerned with balances and imbalances of power. A balanced distribution makes war less likely, while an imbalance increases competition as weaker states ally to counter the dominant state.

Structural realists diverge on whether states should pursue relative gains over competitors or focus on absolute gains. Those focused on relative gains see cooperation as difficult since states worry about losing ground to others. However others argue that states can cooperate for absolute gains as long as it does not produce relative losses. This debate continues to divide structural realists.

Overall, structural realists provide a systemic level of analysis to explain state actions. The configuration of the international system sets limits and incentives for foreign policy, even as leaders retain ultimate decision-making power informed by their perceptions. As such, structural realism remains an influential theory in international relations.

Neoclassical Realism

Neoclassical realism emerged in the late 1990s and early 2000s as an attempt to address some of the perceived shortcomings of structural realism. While structural realists emphasize how the distribution of power in the international system shapes state behavior, neoclassical realists argue that unit-level variables at the state level also need to be considered.

Specifically, neoclassical realism looks at factors like perceptions and misperceptions of power, strategic culture, and domestic politics. While the structure of the international system is still the starting point, neoclassical realists contend that how leaders perceive the system and the internal characteristics of their state will impact how they formulate foreign policy.

For example, different leaders may look at the same distribution of power but come to very different conclusions about the level of threat or opportunity it presents. Their unique perceptions, informed by history and culture, lead to different policy responses. Furthermore, even if leaders accurately perceive the international structure, domestic politics may constrain their available policy options.

By incorporating unit-level variables, neoclassical realists seek to complement the structural emphasis of Kenneth Waltz and other neorealists. They argue that both system-level and unit-level factors are necessary to fully explain states’ foreign policy choices. This provides a more contingent theoretical framework while still retaining core realist assumptions about anarchy and power politics.

Case Study: U.S. Strategic Partnerships with ‘Friendly’ Dictators

The United States’ strategic partnerships with authoritarian regimes in the Middle East provide an illustrative case study of realist international relations theory in practice.

For decades, successive American administrations privileged stability and the preservation of U.S. interests over the promotion of democracy and human rights. This led to close partnerships with dictators and monarchs across the Middle East, including Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak, who ruled for nearly 30 years.

These “friendly authoritarians” were seen as crucial bulwarks against anti-Western regimes and Islamic extremism. Providing them with economic and military aid was prioritized over risky democratic openings. As Condoleezza Rice noted in 2005, “for 60 years, my country…pursued stability at the expense of democracy in this region here in the Middle East, and we achieved neither.”

The contradictions of these policies became clear during the 2011 Arab Spring protests. When mass demonstrations broke out against Mubarak’s rule, the United States was caught between upholding its democratic values and preserving a reliable partner. The Obama administration eventually abandoned Mubarak, reflecting an idealist shift.

However, the aftermath highlighted realist concerns about regional stability and national interests. Egypt’s democratic transition faltered, giving way to military rule. Meanwhile, the uprisings sparked a regional power struggle between Saudi Arabia and Iran.

This case reveals how realist calculations guided U.S. foreign policy for decades, privileging order and stability over democratic change. However, realism proved insufficient when faced with deep societal transformations during the Arab Spring. The complex legacies of these partnerships and policy trade-offs remain front and center for U.S. strategic thinking in the region.

Conclusion

A dispassionate glimpse into the workings of world politics unveils the enduring significance of the realist tradition, despite valid criticisms. Realism taps into fundamental truths about human nature and international anarchy that have proved remarkably consistent over centuries. While alternate approaches highlight cooperation, institutions, and shared values, realism confronts the unavoidable centrality of power.

States remain the key actors in global affairs, acting to ensure their preservation and maximize relative power. Structural constraints and the security dilemma inevitably shape policy choices, even for democracies. However, domestic politics and perceptions also play a role, underscoring realism’s complexity. Although cooperation occurs, self-interest guides state behavior more often than not.

The prevalence of realist principles, albeit adapted contextually, demonstrates the tradition’s resilience. For instance, the US partnerships with authoritarian regimes to maintain regional influence reveal strategic calculations for national interest. Containment during the Cold War represented another realist grand strategy. China’s expanding naval capabilities and assertiveness in the South China Sea similarly reflect realist maneuvers.

As long as the international system remains anarchic and states prioritize survival, realism will dominate theoretical discourse. Its nuanced evolution through neoclassical realism also strengthens its explanatory power. Realism provides a sober perspective on global affairs, beyond idealism, without negating cooperation. Its longevity testifies to the tradition’s profound insights into the complex workings of world politics.