Understanding Models Of Decision Making In Foreign Policy Analysis

Why we should study Foreign Policy Analysis?

FPA examines the decision-making process involved in making foreign policy, including the key actors, institutions, beliefs, perceptions, and domestic and international pressures that influence policy choices. It seeks to shed light on how and why foreign policy decisions are made.

At its core, FPA seeks to understand and explain the causes and consequences of foreign policy decisions. It is an interdisciplinary field, drawing on theories and insights from psychology, sociology, economics, history, and other fields to enrich explanations for foreign policy behavior.

Some key questions examined in FPA include:

- How do domestic politics and institutions shape foreign policy decisions?

- What role do individual leaders and their beliefs play in foreign policy choices?

- How do states perceive and misperceive each other?

- Why do conflicts between states emerge and how are they resolved?

- How and why do foreign policies change over time?

By studying real-world cases, FPA scholars build and test theories about foreign policy decision-making and behavior. The goal is to develop generalized explanations for why states act the way they do in the international arena.

The differences of FPA before and after 1950

Before the 1950s, Foreign Policy Analysis (FPA) primarily focused on the outcomes and outputs of foreign policy decisions. Analysts sought to describe and explain the foreign policies that states pursued without much consideration for the underlying decision-making process. The analytical focus was on what policies states adopted rather than how and why they made those decisions.

After the 1950s, FPA underwent significant changes as the field incorporated insights from cognitive and social psychology.

In essence, post-1950s FPA adopted a decision-making approach focused on comprehending the inputs, process, and outputs of foreign policy. Analysts aimed to elucidate the cognitive patterns, biases, motivations, and perceptions of decision-makers that drive state behavior. This contrasted sharply with pre-1950s FPA that simply looked at foreign policy outputs devoid of process analysis.

Biases on Decision-Making Process

Decision makers often encounter cognitive biases that influence their judgements during policy making. These biases stem from the inherent limitations in human cognition and perception. Some common biases include:

Cognitive Biases

- Focusing on short-term benefits rather than considering longer-term consequences. Leaders may opt for quick wins rather than solutions that require more time and effort.

- Preference for past choices - Leaders often prefer alternatives that are in line with their previous decisions, even if new options may be more beneficial.

- Single alternative focus - Fixating on only one policy option rather than considering multiple alternatives. This narrow focus can overlook better solutions.

- Wishful thinking - Leaders tend to favor outcomes they desire, leading them to subjectively assess options and risks.

- Overconfidence - Overestimating one’s own abilities while underestimating challenges or opponents. This hubris leads to risky gambles based on false self-assurance.

- Groupthink - Conformity to a consensus view in a group that discourages dissenting opinions. This convergence leads to poor decisions going unchallenged.

- Selective information processing - Paying attention to facts that reinforce pre-existing positions while ignoring contradicting evidence. This bias entrenches beliefs and dismisses critical analysis.

Types of Decision

One major way to classify foreign policy decisions is based on their timeframe and relationship to other decisions. The main types include:

- One-shot (single) decisions: These are isolated, non-repeated decisions that the policymaker makes only once. Examples could include recognizing a new government after a coup, or deciding to go to war. They do not directly connect to past or future decisions.

- Interactive decisions: These involve repeated interactions between two or more states in an ongoing relationship, like negotiations or arms races. The interactions are interdependent, so each decision influences the next one. For example, two states engaging in a series of negotiations have interactive decisions, where offers in one round impact the next.

- Sequential decisions: These are a series of decisions that are related over time but made individually rather than interactively. Early choices set the context for later ones. An example could be a state deciding first whether to seek nuclear weapons, next whether to test them, and then later whether to deploy them. Each choice sets the stage for the next phase.

- Sequential-interactive decisions: The most complex type, these combine sequential choices by one policymaker with interactive decisions vis-a-vis another actor. For instance, an extended conflict has sequential decisions within each government about their military strategy combined with interactive exchanges like ceasefire offers between the governments.

Model of Decision-Making

Rational Actor Model (RAM)

The Rational Actor Model (RAM) assumes that decision makers are rational actors who make policy choices based on a rational calculation of costs and benefits. According to RAM, leaders identify foreign policy problems, determine goals, gather information, develop alternative solutions, analyze the costs and benefits of each alternative, and select the optimal policy option that maximizes benefits.

RAM has its roots in economics and uses concepts such as utility maximization to model decision making. It assumes that actors have consistent, ordered preferences and make decisions systematically based on available information. However, RAM has limitations. Critics argue that real-world policymaking rarely follows such a linear, rational process due to cognitive limitations and time constraints. The theory of bounded rationality recognizes that rationality is limited by the information available, cognitive limitations, and time constraints.

The steps of Rational Model of Decision Making

A set of steps in the rational model (Greg Crashman,1993) :

- Identify problem

- Identify and rank goals (preferences)

- Gather information (this can be ongoing)

- Identify alternatives for reaching goals

- Analyze alternatives by considering consequences and effectiveness (costs and benefits) of each alternative and probabilities associated with success (transitivity)

- Select alternative that maximizes chances of selecting best alternative as determined in step five

- Implement decision

- Monitor and evaluate

Game Theory Model (GTM)

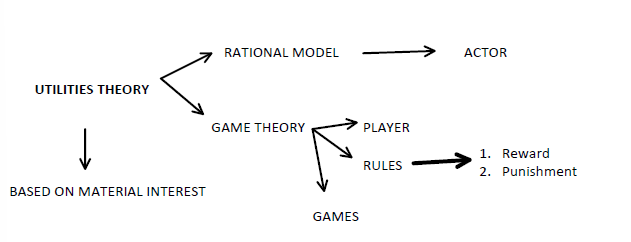

The Game Theory Model (GTM) views foreign policy decisions as strategic choices made in an interactive decision making environment. GTM uses game theory and concepts like payoffs, strategies, and equilibria to analyze decision making. It examines how a state’s foreign policy is shaped by strategic interactions with other states.

According to GTM, leaders look at domestic politics and international systemic factors when making decisions. GTM has been used to analyze decisions made by states, terrorist groups, and governments. It simplifies complex state relationships into strategic games with equilibria. GTM provides insights into counterintuitive behaviors between states based on their interdependent decisions.

In every game in game theory there are 3 components, namely Actor, Strategy and Rules. These rules can also be in the form of rewards or punishments for actors. In game theory there is also equilibrium, namely ‘the outcome that most likely’

Some key game theory models used in foreign policy analysis are Prisoner’s Dilemma and Chicken Game. These models have implications for strategies like precommitment and brinkmanship in foreign policy. Tit-for-Tat is a game theory strategy that promotes cooperation based on reciprocity. Overall, GTM views foreign policy decisions as strategic choices shaped by both domestic and international factors. It provides a systematic way to analyze interactive decision making.

Prisoner’s Dilemma

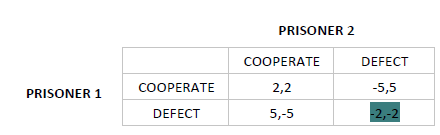

Prisoner’s dilemma is an example of a game in game theory and uses one-shot decision making and there are 2 actors. Analysis of this dilemma can provide insights into how states and other actors make decisions under constrained information.

Analysis example:

In the prisoner’s dilemma, there are two suspects who are questioned separately by the police. Each suspect has a choice - they can either accept the police’s offer to testify against their partner, or they can refuse and remain loyal. This decision is made with limited information since the suspects do not know what choice the other will make and cannot communicate beforehand.

Strategy:

- They can accept the offer offered by the police. This means they testify and confront each other against their fellow suspects

- They can refuse the police’s offer and remain loyal to their partners (other suspects). Remaining loyal may have many drawbacks because other suspects are not guaranteed to do the same

Because the players do not know the other’s decision, they will choose the option that gives them the best personal outcome, which is to accept the deal and testify. This is called minimax behavior - both players avoid the worst possible outcome from the other’s choices. Since both suspects testify, the police do not need to offer a generous deal.

However, if the prisoners could communicate before deciding, they could agree to both reject the deal and refrain from testifying against each other, preventing the police from connecting them to additional crimes. The inability to coordinate decisions results in a less optimal outcome for both prisoners.

Application in prisoner’s dilemma:

Payoffs (possible outcomes):

- -5: this is the worst result, the suspect who gets this will get a heavy sentence because the other suspect gave the police testimony about himself

- -2 : this is better than the worst. The suspect still felt the loss because he had to be imprisoned for a while as a result of being determined by the police to have committed a lesser crime

- 2 : this result is slightly better because the suspect accepted the police’s offer of a deal and was offered leniency

- 5: a suspect who accepts an offer of agreement by the police gets the best results if the other suspect refuses to cooperate and rejects the police’s offer and cooperates with the other suspect

Chicken Game

Chicken Game is a model used in game theory to analyze decision making between two actors in a high stakes situation. The premise is that two actors engage in a dangerous act, and whoever “swerves” or backs down first is the loser. This tests resolve and willingness to accept risk.

Some key aspects of Chicken Game are:

- Brinkmanship - the strategy of pushing a dangerous situation to the brink of catastrophe in order to force the other actor to back down. This tests nerves and resolve.

- Precommitment - the act of committing to a course of action by eliminating your own ability to back out. This signals to the other actor that you will not swerve or back down.

A classic example is the nuclear arms race during the Cold War. The US and Soviet Union continued building larger and larger stockpiles of nuclear weapons to signal their resolve. Neither wanted to be the first to back down from the arms race, but if neither did, the result could be mutual nuclear annihilation.

Chicken Game illustrates how ego, reputation, and domestic political pressure can cause states to engage in risky brinkmanship despite potentially catastrophic outcomes. Understanding Chicken Game dynamics can shed light on nuclear deterrence, territorial disputes, outbreaks of war, and other foreign policy challenges involving reputational stakes and high risks.

Analysis example:

2 car drivers drive their cars facing each other. And they drive each other straight. The one who turns his car first loses.

• If both cars swerve each other, they both lose but prevent the worst outcome, namely a collision. • If only 1 driver swerves his car, he loses more than if both drivers swerve their car.

Ranked :

- Winner (other drivers avoid)

- Survivor (both avoid)

- Sucker (other driver wins)

- Crash (no one avoids it)

Example of a real life case: nuclear

To win the Chicken Game, a player must do whatever it takes to win and avoid losing, this is called ‘precommitment’. In the analysis example, this can be done by deactivating the driver’s steering wheel. This is a signal to other players that they will not shy away. Because of this, Chicken Game has implications for ‘brinkmanship’. Brinkmanship is the act of pushing a dangerous situation to the brink of destruction in order to gain maximum profit and prevent other players from avoiding it.

Tit-For-Tat

The tit-for-tat strategy is a game theory approach that confronts the challenges presented in the prisoner’s dilemma analysis. This strategy aims to create the best possible outcome for both prisoners in the prisoner’s dilemma scenario.

The outline of the tit-for-tat strategy is:

- When arrested for the first time, do not betray your partner.

- When caught again: do what the other player did when they were previously caught. If they betrayed you, betray them back. If they cooperated, cooperate back.

In essence, tit-for-tat is a cooperative strategy based on mutual retaliation. The goal is to incentivize cooperation from the other player through a “one betrayal for one betrayal” approach. If the other player cooperates, you cooperate back to reward and encourage that behavior. If they betray, you betray back to punish the behavior.

The tit-for-tat thinking involves:

- Never being the first to betray your partner.

- Only retaliating after the other player has already betrayed you first.

- Forgiving after a single retaliation.

This sets up a reciprocal system of retaliation that aims to maximize cooperation between the two prisoners. The winner is the prisoner who can effectively cooperate while also punishing betrayals when absolutely required. By balancing cooperation and measured retaliation, the tit-for-tat strategy creates the possibility for the best outcome for both players.